Radiocarbon Dating of the Shroud of Turin

by

P. E. Damon,1 D. J. Donahue,2 B.

H. Gore,1 A. L. Hatheway,2 A. J. T. Jull,1 T.

W. Linick,2 P. J. Sercel,2 L. J. Toolin,1

C.R. Bronk,3 E. T. Hall,3

R. E. M. Hedges,

3 R. Housley,3 I. A. Law,3 C.

Perry,3 G. Bonani,4 S. Trumbore,5 W.

Woelfli,4 J. C. Ambers,6 S. G. E. Bowman,6 M.

N. Leese6 & M. S. Tite6

Reprinted from Nature, Vol. 337, No. 6208, pp. 611-615, 16th

February, 1989

Copyright 1989 Macmillan Magazines Ltd. - All Rights

Reserved

Reprinted by permission.

1 - Department of Geosciences,

2 - Department of Physics,

University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721, USA

3 - Research

Laboratory for Archaeology and History of Art, University of Oxford, Oxford,

OX1 3QJ, UK

4 - Institut für Mittelenergiephysik, ETH-Hönggerberg,

CH-8093 Zürich, Switzerland

5 - Lamont-Doherty Geological

Observatory, Columbia University, Palisades, New York 10964, USA

6 -

Research Laboratory, British Museum, London WC1B 3DG, UK

Very small samples from the Shroud of Turin have been dated by

accelerator mass spectrometry in laboratories at Arizona, Oxford and

Zurich. As Controls, three samples whose ages had been determined

independently were also dated. The results provide conclusive evidence

that the linen of the Shroud of Turin is mediaeval.

The Shroud of Turin , which many people believe was used to

wrap Christ's body, bears detailed front and back images of a man who appears

to have suffered whipping and crucifixion. It was first displayed at

Lirey in France in the 1350s and subsequently passed into the hands of the

Dukes of Savoy. After many journeys the shroud was finally brought to

Turin in 1578 where, in 1694, it was placed in the royal chapel of Turin

Cathedral in a specially designed shrine.

Photography of the shroud by Secondo Pia in 1898 indicated

that the image resembled a photographic 'negative' and represents the first

modern study. Subsequently the shroud was made available for scientific

examination, first in 1969 and 1973 by a committee appointed by Cardinal

Michele Pellegrino 1 and then again in 1978 by the Shroud of Turin

Research Project (STURP)2. Even for the first investigation,

there was a possibility of using radiocarbon dating to determine the age of

the linen from which the shroud was woven. The size of the sample then

required, however, was ~500cm, which would clearly have resulted in an

unacceptable amount of damage, and it was not until the development in the

1970s of small gas-counters and accelerator-mass-spectrometry techniques

(AMS), requiring samples of only a few square centimetres, that radiocarbon

dating of the shroud became a real possibility.

To confirm the feasibility of dating the shroud by these

methods an intercomparison, involving four AMS and two small gas-counter

radiocarbon laboratories and the dating of three known-age textile samples,

was coordinated by the British Museum in 1983. The results of this

intercomparison are reported and discussed by Burleigh et

al.3.

Following this intercomparison, a meeting was held in Turin

in September-October 1986 at which seven radiocarbon laboratories (five AMS

and two small gas-counter) recommended a protocol for dating the shroud.

In October 1987, the offers from three AMS laboratories (Arizona, Oxford and

Zurich) were selected by the Archbishop of Turin, Pontifical Custodian of the

shroud, acting on instructions from the Holy See, owner of the shroud.

At the same time, the British Museum was invited to help in the certification

of the samples provided and in the statistical analysis of the results.

The procedures for taking the samples and treating the results were

discussed by representatives of the three chosen laboratories at a meeting at

the British Museum in January 1988 and their recommendations 4 were

subsequently approved by the Archbishop of Turin.

|

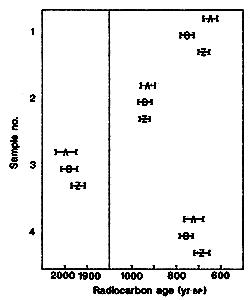

FIG.1 Mean radiocarbon dates, with a ±1 sd (sd

= standard deviation) errors, of the Shroud of Turin and

control samples,

as supplied by the three laboratories (A, Arizona; O, Oxford; Z, Zurich) (See

also Table 2.)

The shroud is sample 1, and the three controls are samples

2-4. Note the break in age scale. Ages are given

in yr BP

(years before 1950). The age of the shroud is obtained as AD 1260-1390,

with at least 95% confidence.

|

Removal of samples from the shroud

The sampling of the shroud took place in the Sacristy at

Turin Cathedral on the morning of 21 April 1988. Among those present

when the sample as cut from the shroud were Cardinal Anastasio Ballestrero (Archbishop

of Turin), Professor L. Gonella (Department of Physics, Turin Polytechnic and

the Archbishop's scientific adviser), two textile experts (Professor F.

Testore of Department of Materials Science, Turin Polytechnic and G. Vial of

Musée des Tissues and Centre International d'Étude des Textiles Anciens in

Lyon), Dr M. S. Tite of the British Museum, representatives of the three

radiocarbon-dating laboratories (Professor P. E. Damon, Professor D. J.

Donahue, Professor E. T. Hall, Dr R. E. M. Hedges and Professor W. Woelfli)

and G. Riggi, who removed the sample from the shroud.

The shroud was separated from the backing cloth along its

bottom left-hand edge and a strip (~10 mm x 70 mm) was cut from just above the

place where a sample was previously removed in 1973 for examination. The

strip came from a single site on the main body of the shroud away from any

patches or charred areas. Three samples, each ~50 mg in weight, were

prepared from this strip. The samples were then taken to the adjacent

Sala Capitolare where they were wrapped in aluminium foil and subsequently

sealed inside numbered stainless-steel containers by the Archbishop of Turin

and Dr Tite. Samples weighing 50 mg from two of the three controls were

similarly packaged. The three containers containing the shroud (to be

referred to as sample 1) and two control samples (samples 2 and 3) were then

handed to representatives of each of the three laboratories together with a

sample of the third control (sample 4), which was in the form of threads.

All these operations, except for the wrapping of the samples in foil and their

placing in containers, were fully documented by video film and photography.

The laboratories were not told which container held the

shroud sample. Because the distinctive three-to-one herringbone twill

weave of the shroud could not be matched in the controls, however, it was

possible for a laboratory to identify the shroud sample. If the samples

had been unravelled or shredded rather than being given to the laboratories as

whole pieces of cloth, then it would have been much more difficult, but not

impossible, to distinguish the shroud sample from the controls. (With

unravelled or shredded samples, pretreatment cleaning would have been more

difficult and wasteful.) Because the shroud had been exposed to a wide range

of potential sources of contamination and because of the uniqueness of the

samples available, it was decided to abandon blind-test procedures in the

interests of effective sample pretreatment. But the three laboratories

undertook not to compare results until after they had been transmitted to the

British Museum. Also, at two laboratories (Oxford and Zurich), after

combustion to gas, the samples were recoded so that the staff making the

measurements did not know the identity of the samples.

ControlsThe three control samples, the approximate ages of which were

made known to the laboratories, are listed below. Two were in the

form of whole pieces of cloth (samples 2 and 3) and one was in the form of

threads (sample 4).

Sample 2. Linen (sample QI.T/32) from a tomb

excavated at Qasr Ibrîm in Nubia by Professor J. M. Plumley for the Egypt

Exploration Society in 1964. On the basis of the Islamic embroidered

pattern and Christian ink inscription, this linen could be dated to the

eleventh to twelfth centuries AD.

Sample 3. Linen from the collection of the Department

of Egyptian Antiquities at the British Museum, associated with an early second

century AD mummy of Cleopatra from Thebes (EA6707). This linen was dated

in the British Museum Research Laboratory using liquid scintillation counting,

giving a radiocarbon age of 2,010 ± 80 yr BP (BM-2558). This

corresponds to a calendar age, rounded to the nearest 5 years, of 110 cal BC -

AD 75 cal at the 68 per cent confidence level 5 (where cal denotes

calibrated radiocarbon dates).

Sample 4. Threads removed from the cope of St

Louis d'Anjou which is held in a chapel in the Basilica of Saint-Maximin, Var,

France. On the basis of the stylistic details and the historical

evidence the cope could be dated at ~ AD 1290 - 1310 (reign of King Phillipe

IV).

Measurement proceduresBecause it was not known to what degree dirt,

smoke or other contaminants might affect the linen samples, all three

laboratories subdivided the samples, and subjected the pieces to several

different mechanical and chemical cleaning procedures.

All laboratories examined the textile samples microscopically

to identify and remove any foreign material. The Oxford group cleaned

the samples using a vacuum pipette, followed by cleaning in petroleum ether

(40° C for 1 h) to remove lipids and candlewax, for example. Zurich

precleaned the sample in an ultrasonic bath. After these initial

cleaning procedures, each laboratory split the samples for further treatment.

The Arizona group split each sample into four subsamples.

One pair of subsamples from each textile was treated with dilute HCL, dilute

NaOH and again in acid, with rinsing in between (method a). The second

pair of subsamples was treated with a commercial detergent (1.5% SDS),

distilled water, 0.1% HCL and another detergent (1.5% triton X-100); they were

then submitted to a Soxhlet extraction with ethanol for 60 min and washed with

distilled water at 70° C in an ultrasonic bath (method b).

The Oxford group divided the precleaned sample into three.

Each subsample was treated with 1M HCL (80° C for 2h), 1M NaOH (80° C for 2

h) and again in acid, with rinsing in between. Two of the three samples

were then bleached in NaOCL (2.5% at pH-3 for 30 min).

The Zurich group first split each ultrasonically cleaned

sample in half, with the treatment of the second set of samples being deferred

until the radiocarbon measurements on the first set had been completed.

The first set of samples was further subdivided into three portions.

One-third received no further treatment, one-third was submitted to a weak

treatment with 0.5% HCL (room temperature), 0.25% NaOH (room temperature) and

again in acid, with rinsing in between. The final third was given a

strong treatment, using the same procedure except that hot (80° C) 5% HCL and

2.5% NaOH were used. After the first set of measurements revealed no

evidence of contamination, the second set was split into two portions, to

which the weak and strong chemical treatments were applied.

All of the groups combusted the cleaned textile subsample

with copper oxide in sealed tubes, then converted the resulting CO2

to graphite targets. Arizona and Oxford converted CO2 to CO

in the presence of zinc, followed by iron-catalysed reduction to graphite, as

described in Slota et al. 6. Zurich used

cobalt-catalysed reduction in the presence hydrogen, as described by Vogel

et al. 7,8.

Each laboratory measured the graphite targets made from the

textile samples, together with appropriate standards and blanks, as a group (a

run). Each laboratory performed between three and five independent

measurements for each textile sample which were carried out over a time period

of about one month. The results of these independent measurements (Table

1) in each case represent the average of several replicate measurements made

during each run (samples are measured sequentially, the sequence being

repeated several times). The specific measurement procedures for each

laboratory are given by Linick et al. 9 for Arizona, by

Gillespie et al. 10 for Oxford and by Suter et al.

11 for Zurich. Arizona and Oxford measured

14C/13C ratios by AMS and determined the

13C/12C ratios using conventional mass spectrometry.

Zurich determined both 14C/12C and

13C/12C quasi-simultaneously using AMS only.

The conventional radiocarbon ages were all calculated using

the procedures suggested by Stuiver and Polach12, with

normalization to Ó13C = -25 0/00, and were accordingly reported in yr BP (years before

1950). The errors, which are quoted in Table 1 at the 1sd level

(

sd is standard deviation), include the statistical (counting) error,

the scatter of results for standards and blanks, and the uncertainty in the Ó13C

determination (Arizona includes the Ó13C error at a later stage,

when combining subsample results; Oxford errors below 40 yr are rounded up to

40).

Table 1 Basic Data (individual measurements)

| |

Sample 1 |

Sample 2 |

Sample 3 |

Sample 4 |

Pretreatment and

replication codes |

| Arizona |

AA-3367 |

AA-3368 |

AA-3369 |

AA-3370 |

|

| |

A1.1b* |

591±30 |

A2.1b |

922±48 |

A3.1b |

1,838±47 |

A4.1b |

724±42 |

|

| |

A1.2b |

690±35 |

A2.2a |

986±56 |

A3.2a(1) |

2,041±43 |

A4.2a |

778±88 |

a, method a |

| |

A1.3a |

606±41 |

A2.3a(1) |

829±50 |

A3.3a |

1,960±55 |

A4.3a(1) |

764±45 |

b, method b |

| |

A1.4a |

701±33 |

A2.4a(2) |

996±38 |

A3.4a(2) |

1,983±37 |

A4.4a(2) |

602±38 |

( ), same subsample |

| |

A2.5b |

894±37 |

A3.5b |

2,137±46 |

A4.5b |

825±44 |

|

| Ó13C (0/00) |

|

-25.0 |

|

-23.0 |

|

-23.6 |

|

-25.0 |

|

| |

| Oxford |

2575 |

2574 |

2576 |

2589 |

|

| |

O1.1u |

795±65 |

O2.1u |

980±55 |

O3.1u |

1,955±70 |

O4.2u |

785±50 |

u, unbleached |

| |

O1.2b |

730±45 |

O2.1b |

915±55 |

O3.1b |

1,975±55 |

O4.2b(1) |

710±40 |

b, bleached |

| |

O1.1b |

745±55 |

O2.2b** |

925±45 |

O3.2b |

1,990±50 |

O4.2b(2) |

790±45 |

( ), same pretreatment/

run

combination |

| Ó13C***(0/00) |

|

-27.0 |

|

-27.0 |

|

-27.0 |

|

-27.0 |

|

| |

| Zurich |

ETH-3883 |

ETH-3884 |

ETH-3885**** |

ETH-3882 |

|

| |

Z1.1u |

733±61 |

Z2.1u |

890±59 |

Z3.1u |

1,984±50 |

Z4.1u |

739±63 |

|

| |

Z1.1w |

722±56 |

Z2.1w |

1,036±63 |

Z3.2w |

1,886±48 |

Z4.1w |

676±60 |

u, ultrasonic only |

| |

Z1.1s |

635±57 |

Z2.1s |

923±47 |

Z3.2s |

1,954±50 |

Z4.1s |

760±66 |

w, weak |

| |

Z1.2w |

639±45 |

Z2.2w |

980±50 |

|

Z4.2w |

646±49 |

s, strong |

| |

Z1.2s |

679±51 |

Z2.2s |

904±46 |

|

Z4.2s |

660±46 |

|

| ÓC***** (0/00) |

|

-25.1 |

|

-23.6 |

|

-22.0 |

|

-25.5 |

|

In years BP,

corrected for Ó13C fractionation; errors at 1 sd level; see text

for pretreatment details.

* The identification

code for each measurement shows, in order, the laboratory, sample, measurement

run, pretreatment and any replication involved.

** One anomalous replicate (of 6) obtained for independent

measurement O2.2b; if rejected it reduces date by 40 yr; final date quoted

actually reduced by 20 yr.

*** Measured for

samples 1 and 3; assumed for samples 2 and 4.

**** The loose weave of sample Z3.1 led to its disintegration during

strong and weak chemical treatments. Z3.2 was centrifuged to avoid the

same loss of material.

***** Average of

separate determinations by AMS.

Results

On completion of their measurements, the laboratories

forwarded their results to the British Museum Research Laboratory for

statistical analysis. The individual results as supplied by the

laboratories are given in Table 1. Each date represents a unique

combination of pretreatment and measurement run and applies to a separate

subsample, except where indicated by the identification code. From these

data it can be seen that, for each laboratory, there are no significant

differences between the results obtained with the different cleaning

procedures that each used.

Table 2 Summary of mean radiocarbon dates and assessment of

interlaboratory scatter

| Sample |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| Arizona |

646 ± 31 |

927 ± 32 |

1,995 ± 46 |

722 ± 43 |

| Oxford |

750 ± 30 |

940 ± 30 |

1,980 ± 35 |

755 ± 30 |

| Zurich |

676 ± 24 |

941 ± 23 |

1,940 ± 30 |

685 ± 34 |

| |

| Unweighted mean* |

691 ± 31 |

936 ± 5 |

1,972 ±16 |

721 ± 20 |

| Weighted mean** |

689 ± 16 |

937 ± 16 |

1,964 ± 20 |

724 ± 20 |

| X 2 value (2 d.f.) |

6.4 |

0.1 |

1.3 |

2.4 |

| Significance *** level (%) |

5 |

90 |

50 |

30 |

Dates are in yr BP. d.f., degrees of freedom.

* Standard errors based on scatter.

**

Standard errors based on combined quoted errors.

*** The probability of obtaining, by chance, a scatter among the three

dates as high as that observed, under the assumption that the quoted errors

reflect all sources of random variation.

The mean radiocarbon dates and associated uncertainties for

the four samples, as supplied by each of the three laboratories, are listed in

Table 2 and shown in Fig.1. Also included in Table 2 are the overall

unweighted and weighted means, the weights being proportional to the inverse

squared errors as quoted by the laboratories. The underlying principle

of the statistical analysis has been to assume that, unless there is strong

evidence otherwise, the quoted errors fully reflect all sources of error and

that weighted means are therefore appropriate. An initial inspection of

Table 2 shows that the agreement among the three laboratories for samples 2, 3

and 4 is exceptionally good. The spread of the measurements for sample 1

is somewhat greater than would be expected from the errors quoted.

More quantitatively, to establish whether the scatter among

the three laboratory means was consistent with their quoted errors, a X2

test was applied to the dates for each sample, in accordance with the

recommended procedure of Ward and Wilson 13. The results of

this test, given in Table 2, show that it is unlikely that the errors quoted

by the laboratories for sample 1 fully reflect the overall scatter. The

errors might still reflect the uncertainties in the three dates relative to

one another, but in the absence of direct evidence on this, it was decided to

give the three dates for sample 1 equal weight in determining the final mean,

and to estimate the uncertainty in that mean from the scatter of results.

As shown in Table 2, the unweighted mean of the radiocarbon

age of sample 1 and its uncertainty are 691 ± 31 yr BP. The confidence

limits for sample 1 were obtained by multiplying the uncertainty by

td, the value of a Student's t distribution with d

degrees of freedom at the appropriate probability level. The value

of d, which lies between the inter- and intra-laboratory degrees of

freedom -- that is, between 2 and 9 -- was estimated at 5 on the basis of an

analysis of variance on the 12 individual measurements supplied by the

laboratories 14. Individual measurements from a particular

laboratory were weighted according to their inverse squared errors, but the

contributions from different laboratories were weighted equally, thus ensuring

consistency with Table 2. Thus for sample 1, where the error has been

estimated from the scatter, ~68% and 95% confidence limits for the true

radiocarbon date were found from the 1.1 sd and 2.6 sd errors

about the unweighted mean respectively, the multiplying factors being obtained

from standard tables of the t5 distribution. However,

for samples 2, 3, and 4, the limits were obtained in the usual way from 1

sd and 2 sd quoted errors about the weighted means, assuming

normality.

|

The calendar-age ranges which correspond to the radiocarbon

confidence limits are show in Table 3. These were determined from the

high-precision curve of Stuiver and Pearson 5 based on

dendrochronological dating. Method A (the intercept method) in revision 2.0 of

the University of Washington Quaternay Isotope Laboratory Radiocarbon

Calibration Program 15 was used. In this method, the error

in the calibration curve is first incorporated into the radiocarbon error,

thus widening the limits on the radiocarbon scale slightly; calendar ages are

then found that correspond to these limits, without transforming the complete

probability distribution of radiocarbon dates. No additional uncertainty

has been added to take account of the short growth period of textile samples.

There is little published guidance on this, although it has been suggested

that 15 years should be added in quadrature to the overall uncertainty in the

radiocarbon date for samples of growth period less than one year, such as

linen. In general, such additional uncertainty would widen the 95%

calendar limits by ~ 2 - 4 years at either end, except for sample 3 where the

9 cal BC limit would be changed to 34 cal BC.

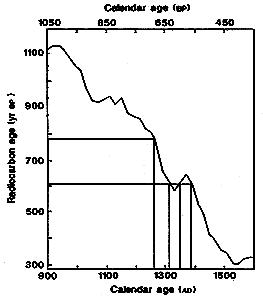

The 95% limits for the shroud are also illustrated in Fig. 2,

where it is apparent that the calibration of the radiocarbon date for sample 1

gives a double range. The correct transformation of probability

distributions from the radiocarbon to the calendar scale is still subject to

debate, there being two different methods of dealing with multiple intercepts.

However, both methods agree that the major probability peak lies in the

earlier of the two ranges, in the 68% range at the end of the thirteenth

century. Sample 4 has a very narrow calendar range: this is due to the

steep slope in the calibration curve at this point, and is an occasional

instance of calibration reducing rather than increasing a confidence

range. Sample 3 compares well with the date obtained by conventional

radiocarbon dating; there is no evidence for a difference between the two

results. The dates for samples 2 and 4 agree with the historical

evidence, which places them in the eleventh to twelfth centuries and late

thirteenth/early fourteenth centuries AD respectively.

The results, together with the statistical assessment of the

data prepared in the British Museum, were forwarded to Professor Bray of the

Istituto di Metrologia 'G. Colonetti', Turin, for his comments. He

confirmed that the results of the three laboratories were mutually compatible,

and that, on the evidence submitted, none of the mean results was questionable.

Table 3 Calibrated date ranges at the 68% and 95% confidence

levels

| Sample |

Mean Date (yr BP) |

|

Calendar date ranges |

| 1* |

691 ± 31 |

68% |

AD 1273 - 1288 |

| |

95% |

AD 1262 - 1312, 1353 - 1384 cal |

| 2 ** |

937 ± 16 |

68% |

AD 1032 - 1048, 1089 - 1119, 1142 - 1154

cal |

| |

95% |

AD 1026 - 1160 cal |

| 3** |

1,964 ± 20*** |

68% |

AD 11-64 cal |

| |

95% |

9 cal BC - AD 78 cal |

| 4** |

724 ± 20 |

68% |

AD 1268 - 1278 cal |

| |

95% |

AD 1263 - 1283

cal |

* Confidence

limits on the radiocarbon scale found from the standard error on the

unweighted mean, assuming a t5 distribution (multiplying

factors 1.1 and 2.6 for 68% and 95% respectively). Standard error estimated

from scatter.

** Confidence limits on the radiocarbon

scale found from the standard error on the weighted mean, assuming a normal

distribution (multiplying factors 1 and 2 for 68% and 95% limits

respectively). Standard error computed from quoted errors.

*** Date by convential radiocarbon dating at

the British Museum: 2010 ± 80 yr. BP (MB - 2558).

ConclusionsThe results of radiocarbon measurements at Arizona, Oxford

and Zurich yield a calibrated calendar age range with at least 95% confidence

for the linen of the Shroud of Turin of AD 1260 - 1390 (rounded down/up to

nearest 10 yr). These results therefore provide conclusive evidence that

the linen of the Shroud of Turin is mediaeval.

The results of radiocarbon measurements from the three

laboratories on four textile samples, a total of twelve data sets, show that

none of the measurements differs from its appropriate mean value by more than

two standard deviations. The results for the three control samples agree

well with previous radiocarbon measurements and/or historical dates.

We thank Cardinal Anastasio Ballestrero for allowing us

access to the shroud, Professor L. Gonella for his help and support

throughout the project and Professor A. Bray for commenting on our statistical

assessment of the data. We also thank Miss E. Crowfoot, T. G. H. James,

Dr J. Evin, M. Prevost-Macillacy, G. Vial, the Mayor of Saint-Maximin

and the Egypt Exploration Society for assistance in obtaining the three

known-age control samples. Oxford thank P. H. South (Precision Process

(Textiles) Ltd, Derby) for examining and identifying the cotton found on the

shroud sample; R. L. Otlet (Isotopes Measurement Laboratory, AERE, Harwell)

for stable isotope ratio measurements on two samples; J. Henderson and the

Department of Geology, Oxford Polytechnic for undertaking scanning electron

microscopy, and SERC for the Special Research Grant which provided the primary

support for the Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit. Zurich thank the Paul

Scherrer Institut (PSI, CH-5234 Villigen) for technical and financial

support. The AMS Programme at Arizona is partially supported by a grant

from the NSF.

- La S. Sindone-Ricerche e studi della Commissione di Esperti nominata

dall' Arcivescovo di Torino, Cardinal Michele Pellegrino, nel 1969

Supplemento Rivista Diocesana Torinese (1976).

- Jumper, E.J. et al. in Archaeological Chemistry-III (ed.

Lambert, J. B.) 447-476 (Am. chem. Soc., Washington, 1984).

- Burleigh, R., Leese, M. N. & Tite, M.S. Radiocarbon

28, 571-577 (1986).

- Tite, M.S. Nature 332, 482 (1988)

- Stuiver, M. & Pearson, G.W. Radiocarbon 28, 805-838

(1986).

- Slota, P.J., Jull, A. J. T., Linick, T. W. & Toolin, L. J.

Radiocarbon 29, 303-306 (1987).

- Vogel, J. S., Nelson, D.E. & Southon, J.R. Radiocarbon

29, 323-333 (1987).

- Vogel, J. S., Southon, J.R. & Nelson, D.E. Nucl. Instrum.

Meth. B29, 50-56 (1987).

- Linick, T. W., Jull, A. J. T., Toolin, L. J. & Donahue, D. J.

Radiocarbon 28, 522-533 (1986).

- Gillespie, R., Gowlett, J. A. J., Hall, E. T. & Hedges, R. E. M.

Archaeometry 26, 15-20 (1984).

- Suter, M. et. al. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. 233[B5], 117-122

(1984).

- Stuiver, M. & Polach, H. A. Radiocarbon 19, 355-363

(1977).

- Ward, G. K. & Wilson, S. R. Archaeometry 20, 19-31

(1978).

- Caulcott, R. & Boddy, R. Statistics for Analytical Chemists

(Chapman and Hall, London, 1983).

- Stuiver, M. & Reimer, P. J. Radiocarbon 28, 1022-1030

(1986).

IG. 2 Calibration of the overall mean radiocarbon date

for sample 1 (the Shroud of Turin) using the

'intercept' method. (See

also Table 3.) Calibration is necessary because of natural variations in

atmospheric14C.

The calibration curve for the relevant

period is that of Stuiver and Pearson 5, a portion of which is

illustrated.

The uncertainty in the calibration curve has been

combined with the error in the mean radiocarbon date, giving the 95%

confidence

limits on the radiocarbon scale; the error envelope on the curve has

therefore been omitted from the diagram.

The stippled areas show how

the 95% confidence limits are transformed from the radiocarbon to the

calendar scale. | |

![]()